It’s hard to scroll through social media without coming across a medical TikTok. For those who missed it: “Medical TikTok” refers to videos in which healthcare professionals vent about their days or share useful health information.

With more than 1 billion downloads of the app, TikTok is one of the fastest-growing social media platforms, outpacing Facebook, Messenger, and Instagram in 2019. People compare it to Vine (R.I.P.), or you may have known it as musical.ly, a karaoke-like lip-syncing app for videos.

Some medical TikToks read like bite-size after-school specials set to popular music: A conventionally attractive young doctor points to text that shows symptoms of herpes; a nurse lip-syncs to Britany Spears while reminding viewers to get their flu shots.

Last November, a TikTok by a user known as D Rose shared a video in which she imitates a patient who fakes a panic attack. D Rose shared the video on Twitter with the caption “We know when y’all are faking.”

Tweet

As a result of this video, activist and writer Imani Barbarin created the hashtag #PatientsAreNotFaking. Through the hashtag, thousands of people shared their experiences of having their pain or symptoms dismissed by doctors and nurses who assumed they were faking.

Tweet

In another TikTok by user @mursimedical, a healthcare provider in scrubs describes an incident in text bubbles. A 24-year-old patient came into the ER with pains in their chest and arm, saying they thought they were having a heart attack. A thought bubble above her head reads, “Maybe it’s cocaine.” And she rolls her eyes.

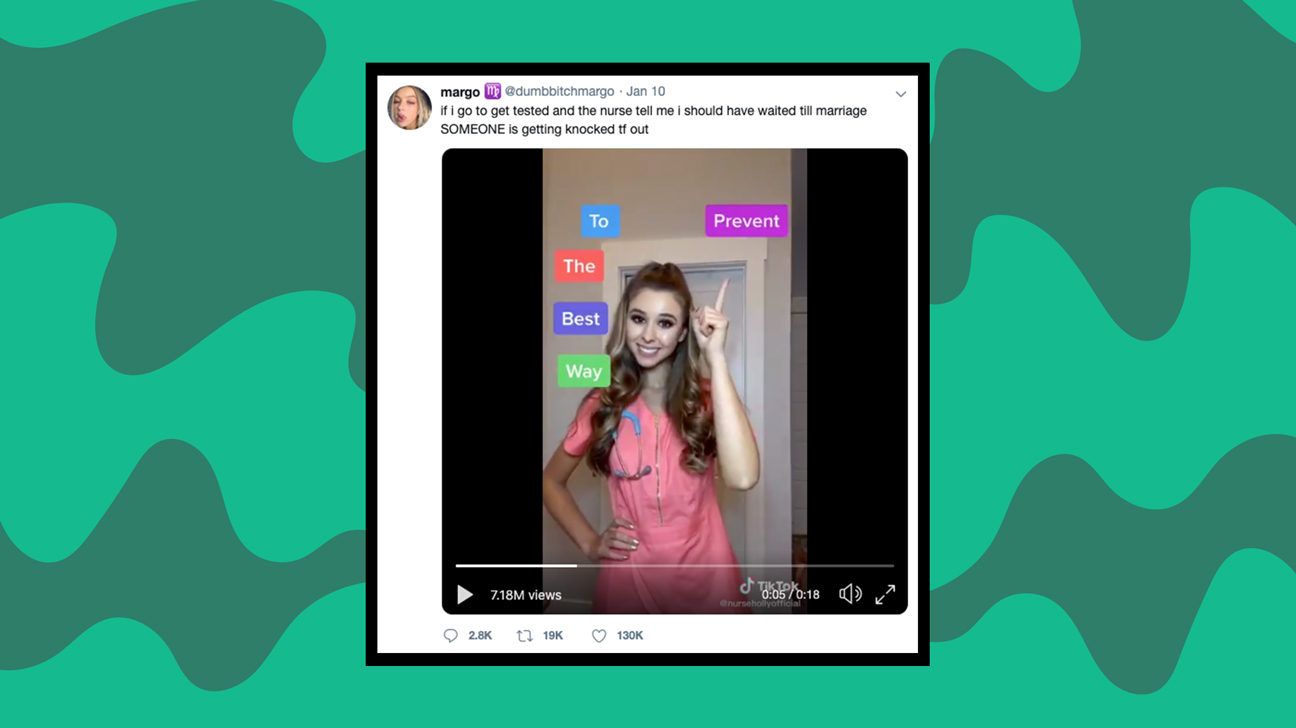

More recently, a viral TikTok by Holly Grace, a nurse with more than 1.7 million TikTok followers, shows her dancing to music in scrubs while pointing to text that reads, “The best way to prevent STDs is waiting for sex until marriage. Just the truth.”

Immediately people pointed out that marriage doesn’t necessarily make sex any “safer.” After all, your spouse may have an STI from a previous relationship or contract one from cheating or from a nonsexual source like blood exposure.

Tweet

Dr. Daniel Atkinson, lead clinician at Treated.com and a general practitioner, calls Holly Grace’s video “irresponsible.”

“Giving the impression that it’s the marriage ceremony that offers protection is dangerous and misleading,” he says. “It is better to be open and honest about the spread of infectious diseases and highlight the importance of practicing safer sex and promoting the use of condoms.”

And what’s more worrying is the thousands of people — some of whom are also healthcare practitioners — who cosign the messages by sharing, liking, or commenting on the videos on various platforms.

“A lot of medical professionals would respond to these TikToks by saying, ‘Oh, I really relate, you’re completely right!’,” says Barbarin. “And you’re thinking, ‘Is this the medical professional I’ll have to go to?’ It’s a camaraderie among medical professionals, but it’s very alienating to patients.”

Naturally, these types of videos have received major backlash.

“I find the trend concerning as a patient,” Barbarin says. “I get the impression that it could discourage some people from talking to [their doctors] when they have concerning symptoms.”

Many Twitter and Facebook users have pointed out how this could discourage people from seeking medical help out of fear that they will be insulted or judged by their doctors. Someone who thinks they may be having a heart attack might be too scared to go into the ER, for example, out of fear that their doctor will make fun of them in front of millions of strangers.

“Attending a doctor’s appointment should be a safe and confidential space, free from judgment,” Atkinson says. “It is distressing that [TikTok] has been skewed by individuals using the platform to miscommunicate or misinform — unfortunately, this is a common practice with the rise of social media.”

For marginalized people who are used to being disbelieved by doctors, seeing this dynamic online is nothing shocking. “It doesn’t make the marginalized fear going to the doctor more; it confirms our fear,” Barbarin says.

Weight stigma, racism, and sexism, as well as other forms of discrimination, can seep into healthcare settings and prevent people from getting necessary care. TikTok just happens to be the platform of the moment, which is why these videos seem so prevalent.

But it’s also the comedic nature of TikTok that makes this trend more unnerving.

While Twitter, Facebook, and even Instagram can take an earnest tone, TikTok is decidedly geared toward more lighthearted and funny content. It’s not simply a doctor accusing a patient of exaggerating in a text post — it’s a video where a doctor is accusing a patient of exaggerating while lip-syncing to Ariana Grande.

For patients who have been discriminated against, Barbarin says, turning this mockery into a joke is all the more infuriating.

What’s more, TikTok’s verification system is based more on popularity and clout. Anybody could buy a stethoscope from the dollar store and pose as a medical professional on the app. TikTok makes it hard to figure out whether a user is really who they say they are.

TikTok may not have created the issue of prejudice in healthcare, but it certainly shines a light on the problem. The mockery is no longer happening behind closed doors, and the misinformation isn’t simply handed from the doctor to one patient.

And Barbarin says these TikToks have kicked off conversations about medical malpractice.

“I’m glad for these videos in a way, because people otherwise don’t believe you when you say that doctors have mocked your pain or told you that you were faking,” Barbarin says. “It also showed the volume of the issue. The only reason why #PatientsAreNotFaking was so successful is because a lot of people had those experiences.”

The nature of the internet means controversial videos are more likely to go viral than ones that simply offer true, helpful information. But that doesn’t mean helpful TikToks aren’t out there. TikTok can be a great way to reach people — especially younger people — and share vital health information.

In fact, Barbarin says, there is space for healthcare professionals to challenge the discrimination shown by their colleagues — something some medical TikTokkers are already doing. Marginalized users, especially, are calling out and debunking certain misinformation shared on medical TikToks.

Tweet

“I think the real opportunity here is to break down your own biases in front of the camera,” Barbarin says. “If you come to some kind of realization about medical care and marginalized people, you need to say that out loud. Not many people see that sort of accountability and responsibility from people in a profession that’s so revered.”

“Using TikTok to debunk medical myths, and speak to its users in a way they can understand about medical problems they may be worried about, is great,” says Atkinson. “It’s important to praise those who are creating this content for a younger audience as much as highlighting those who create misinformed videos.”

Controversial medical TikToks are highlighting a problem that has existed for decades — centuries, even. Let’s hope they can highlight a potential solution too.

Siân Ferguson is a freelance writer and journalist based in Grahamstown, South Africa. Her writing covers issues relating to social justice and health. Find her on Twitter.